I packed water, an apple, and an orange, but no extra layers of clothing. This was Christmas Day. A leisure ride, nothing that was going to kill me. I knew the hill on Higgins Canyon Road from having come down it once by car. Winding and barely wide enough for one car and a bike to pass. Spectacular views of Sky Moon Ranch, the sheep and cattle grazing next to large water reservoirs on steep hillsides.

The route we had chosen would not, we decided in advance, include riding up that part of the road. We would turn off and make a loop back to town, way before that steep ascent. After all, this was Christmas Day. No need to kill ourselves.

The turnoff was, according to the map, just after Burleigh Murray Ranch and off to the right. All we passed were private roads with mailboxes and No Trespassing signs on the right. We kept riding because it was a gorgeous day and it was fun.

Next thing I knew, we were headed up the hill.

I was winded, already climbing, when I began to get the words out about checking the GPS. By the time we found a safe area to pull off the road, we had already climbed several hundred feet. I was already in one of the lower gears. The winding road was laid out in front of us, one short section at a time, only revealing the very next turn, not telling us whether this was the last, or second to last, or how many there would be ahead. No tacit reassurance of “one more to go”, like a personal trainer or aerobics class instructors might provide.

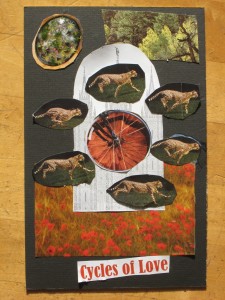

Only the half loop spiraling up and disappearing behind the next bend. So in the moment of riding, there is only the decision to make it around the very next bend. Or not. There is no gratification of “knowing” that if you just do one more of these, you’ll be a rock star. Only the decision, between you and your body, whether to take the bike up one more section of the spiral.

It’s the “Do what’s in front of you” part of going toward your vision. Your bike is pointed in the direction of the top of the hill. Your job, in any given moment, is to pedal up this particular section. Your job is not to “get to the top”. Getting to the top is what happens when you make the decision to see what’s around the next bend, over and over again, and then you look up from what you're doing to discover that you’re at the top.

I remember exactly that moment from this Christmas Day ride, actually. I had just powered up about three sections without rest, after a man twice my age wearing blue jeans had passed us. He was sincere and kind when he said, “Merry Christmas! You guys are doin’ ter-RIF-fic!” I thought to myself, “Not as terrific as YOU are!” and kept pedaling because I couldn’t talk. I bore down a little harder, figuring I wasn’t going to rest my way to being in that kind of shape when I am his age (I guessed 80).

But by the end of the third spiral, I had it in my head that this was it. My limit. If the next climb didn’t bring us to the top, I would turn around. It was Christmas. Why was I killing myself?

I stopped and, panting, leaned on the handle bars of my bike, sucking down water from my CamelBak straw between breaths.

“Is this it?” my riding partner Randy asked.

I couldn’t talk just then. I was feeling the simultaneous sensation that my body was being pushed to a limit, and the sense that I wanted to feel more of this. There was a kind of curiosity and delight about seeing what a little bit more right now would feel like. Even though it was pretty uncomfortable.

So I said, “Go!”, motioning for him to start climbing the next portion. To see what was around the next bend.

I didn’t wait for my heartrate to slow down more or my breathing to recover to normal pace. I started climbing, choosing to go deeper into the “zone beyond comfort” and see where it took me. I didn’t care about the top, I just wanted to keep going and feeling this sensation.

The rhythm of my pedal strokes was slow and steady. My lungs were getting accustomed to the slight burning that accompanied each breath. It took focus ot keep the handlebars in line with the edge of the pavement as I climbed like this. I looked only directly ahead of me. Not toward the top.

And around the next bend, we saw the 80-year-old man come coasting toward us, having reached the top and turned around already. I had no focus left to smile, comment, or register this fact but had to keep pedaling. The last piece of road was a bit of straightaway and the top was marked by an old gate at the base of a eucalyptus tree, with an expanse of downward rolling hills stretched out beyond it.

We were there. The top. It wasn’t something we set out to do. In fact, I had strictly planned otherwise. It was something that happened as a result of deciding, one stretch of road at a time, to keep climbing and see what’s around the next bend.

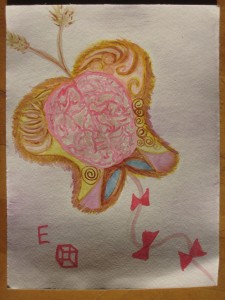

I drew the "Joy" card from the Soul Coaching deck. Its message was to remember that my soul's purpose is simple - to experience joy. And to share this and its healing qualities with the world.

I drew the "Joy" card from the Soul Coaching deck. Its message was to remember that my soul's purpose is simple - to experience joy. And to share this and its healing qualities with the world. It was a foggy, misty morning, but just before 10 o'clock, the sun began to shine.

It was a foggy, misty morning, but just before 10 o'clock, the sun began to shine.

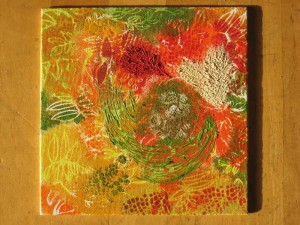

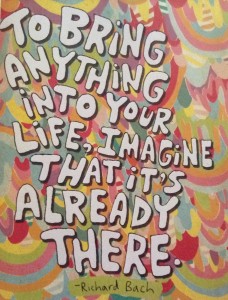

This week's meeting was all about finding the intention that aligns the most with true desire, and then filling every cell of our body with that desire.

But not in the way you might normally think of desire, as "I want".

This week's meeting was all about finding the intention that aligns the most with true desire, and then filling every cell of our body with that desire.

But not in the way you might normally think of desire, as "I want". The stories from the

The stories from the